From reactive to resilient: Building internationalisation strategies in global higher education

How can higher education institutions chart their way forward as the world becomes increasingly disruptive? In this article, we explore how institutions can move beyond reactive strategies and build sustainable internationalisation strategies for the future. Drawing on real-world examples, we focus on diversifying recruitment pipelines, aligning academic offerings with future workforce needs, and rethinking partnerships and policy engagement.

Disruption in global education: Why non-Big Four destinations are gaining popularity

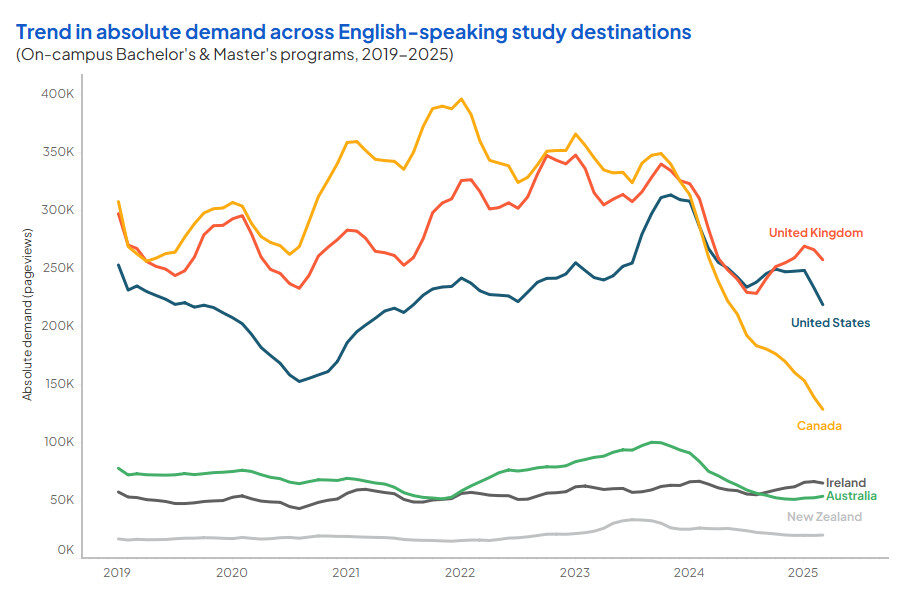

Currently, higher education is being disrupted across the globe. In particular, demand is largely declining for Canada as the student capping system introduced at the start of 2024 led to fewer students viewing Canada as the viable option it once was. Similarly, stricter visa criteria to study in Australia have led to a drop in demand, leading to Ireland now surpassing Australian institutions in terms of student interest. As developments in the US continue to unfold under the Trump administration, the UK and other non-traditional destinations may stand to benefit.

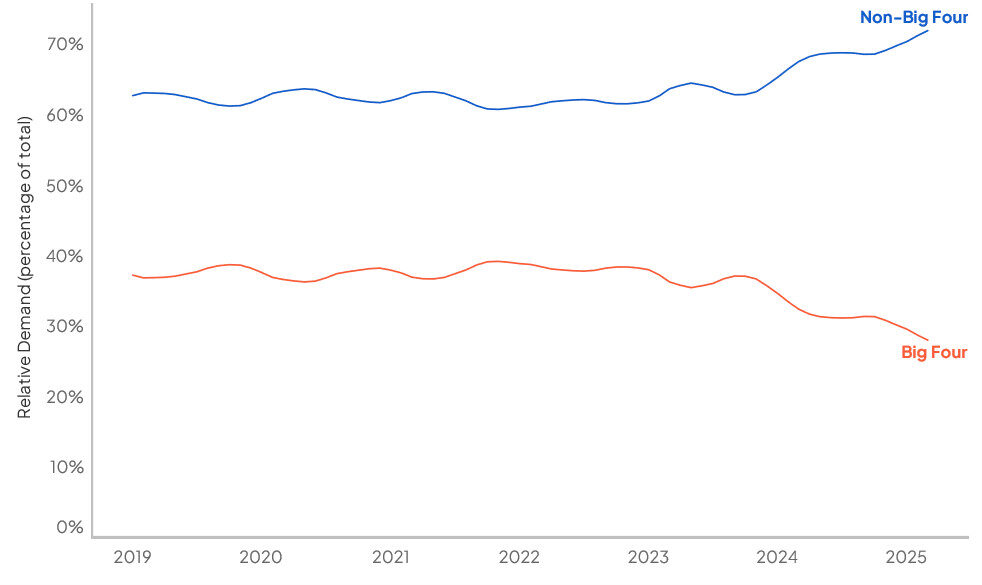

One result of this disruption is the increased demand for non-Big Four destinations, while demand for Big Four destinations declines, causing a widening gap in student interest between the two.

This results from the uncertain atmosphere created by domestic policies in these traditional destinations, and is likely aided by the rise of English-taught Programmes (ETPs) in non-Big Four destinations. According to research by British Council IELTs and Studyportals, one in five English-taught programmes is now found outside of the Big Four destinations.

Daniel Cragg, a Director at Nous Group with a focus on the of Global Higher Education Sector, emphasises the impact of ‘slowbalisation’ —a term coined by The Economistto describe the slowdown in globalisation. He notes that macroeconomic shifts, rising geopolitical tensions, and growing anti-immigration sentiment are making countries more inward-looking. In the context of international education, this phenomenon helps explain why traditional Big Four destinations are becoming less accessible and attractive to international students. As global mobility patterns fragment and regional alternatives gain traction, institutions must adapt their strategies to navigate a world where internationalisation is no longer linear, but increasingly regional, competitive, and shaped by national policy agendas.

As a result of the recent policy shifts, demand to study in Europe, the most popular collective region outside anglophone markets, continues to rise. However, it is clear that demand for study in the education hubs of both Asia and the MENA region is growing rapidly, albeit of a smaller base. Of note, various Asian countries are positioning themselves as education hubs, setting ambitions and goals to attract international students to meet local skill shortages and fend off the issue of aging demographics by using student friendly policies that seek to meet the graduate outcomes, affordable fees, and flexible visa processes. This has had the intended effect as destination Japan witnessed a 117.2% growth in demand by March 2025 compared to January 2019, with significant growth for India (+93.2%), China (+52.1%), Malaysia (+50.9%), and South Korea (+31.2%).

Sustainable growth requires flexibility, clarity, and resilience

To succeed, institutions must take a market-informed, data-driven approach, backed by senior leadership and guided by a clear value proposition. This means developing offerings that are both globally relevant and locally resonant—programmes that not only carry academic weight, but also lead to meaningful employment outcomes and mobility opportunities. Strategic collaboration with host governments and institutions is essential, particularly in navigating regulatory complexities, ensuring community support, and achieving long-term sustainability.

Ultimately, as the global education environment grows more fractured and regionalised, universities must find new ways to be globally engaged without relying solely on physical student movement. TNE offers one of the most promising paths forward—but only for those willing to invest, adapt, and think beyond borders.

Looking ahead, the institutions best positioned to thrive will be those that approach internationalisation not as a transactional pursuit, but as a strategic and adaptive process. Building sustainable, values-aligned partnerships, responding to student needs, and maintaining agility in the face of geopolitical and policy change will be essential. In a shifting global landscape, long-term success will depend on universities’ ability to combine strategic clarity with operational resilience—delivering not just mobility, but impact.

Practical insights: Sustainable strategies for transnational education in a disrupted global landscape

In a breakfast session at APAIE | Asia-Pacific Association for International Education, co-hosted by Studyportals, Nous Group, The PIE and Oxford International Education Group, sector leaders explored real-world examples of how institutions are responding to this disruption and, as a result, tailoring their international strategies. This included insights about transnational education (TNE) as a crucial strategy for universities.

What came through strongly during the session was a growing consensus that TNE must be anchored in sustainable models that deliver mutual benefit. During the session, Kasia Cakala, Director Education Pathways Development at Oxford International Education Group, rightly pointed out that institutions cannot merely ‘plant a flag’ overseas in the hope of brand recognition or short-term revenue. Rather, they are investigating more nuanced, integrated approaches. These include joint or dual degrees, hybrid delivery models, and locally embedded partnerships that align with student needs and labour market demand. Not only do these models continue to offer students the quality and flexibility they desire, but they also allow greater resilience for institutions—particularly when mobility is uncertain.

A strong example of a strategic approach was shared by Meredith Smart, who serves as the International Director for Auckland University of Technology (AUT). AUT has deliberately grounded its internationalisation strategy in sustainable growth with the focus on sustained student volumes through prudent financial planning, diversifying recruitment across programmes and markets, and aligning offerings with current and future employment trends. One crucial factor AUT is leveraging is their active collaboration with government bodies to ensure institutional objectives align with national priorities around talent retention and skilled workforce development.

However, the road to effective TNE is far from straightforward as, despite widespread interest, institutional success remains mixed. Based on a global survey by Nous Groupto over 200 international education leaders in 2024, many universities—particularly those outside the global top 100— indicated their struggle with internal buy-in, risk aversion, and resource constraints. The challenge is compounded by complex regulatory landscapes, which vary significantly by country and can pose major hurdles to implementation. As one respondent from Australia put it, “Onerous application processes and negotiations with local governments” often stall progress. Others pointed to cultural inertia and lack of operational agility as internal barriers that are equally difficult to overcome.

The drivers behind TNE also reveal much about institutional motivations. Survey responses understandably stated that enhancing global profile and generating revenue remain top priorities, with research collaboration and student mobility seen as a secondary priority.

What is clear is that TNE cannot be approached as a transactional exercise. As another panellist for the session, Aziz Boussofiane—Director of Cormack Consultancy Group—aptly put it, ‘TNE should be transformational, not transactional.’ This captured the mood in the room: universities must act as responsible and cooperative partners, mindful that a misstep by one institution can damage the credibility of others operating in the same region, a sentiment that was also shared and echoed by Kasia. Trust, mutual respect, and alignment of values are key to building programmes with true longevity.