MENA is becoming a global education hub. Experts say it needs more than a “Cappuccino strategy”

Professor Thami Ghorfi, President of ESCA Ecole de Management in Morocco, described a pattern he has seen among some foreign universities entering the region. Many institutions, he argued, arrive offering only executive education, MBAs, or short professional programmes — the “foam” and “cream” of the market — while avoiding the harder, more foundational work of delivering full undergraduate programmes, local engagement, or research.

This, he said, is the cappuccino strategy:

“They come, they get the foam and the cream from the cappuccino and delete the black coffee.”

The “black coffee” represents deeper commitments:

- full-time faculty

- research and knowledge creation

- undergraduate education

- societal contribution

- integration into local ecosystems

Institutions that only take the top slice of the market face “less risk,” he explained — but also bring less value. By contrast, the universities that establish full undergraduate and graduate campuses “do better,” elevate quality, and improve the wider ecosystem through accreditation, rankings, and competition. Foreign universities need to contribute meaningfully, not just operate satellite operations for revenue.

Historically, institutions entered the Gulf mainly to “get international students in” without integrating into local priorities. Today, governments want students to stay, contribute to the workforce, and support economic transformation. Research, innovation, and employability are becoming central — not optional extras. This aligns with broader changes in global mobility as students look beyond traditional destinations amid rising costs and visa uncertainty.

The region’s momentum is real — If the strategy is right

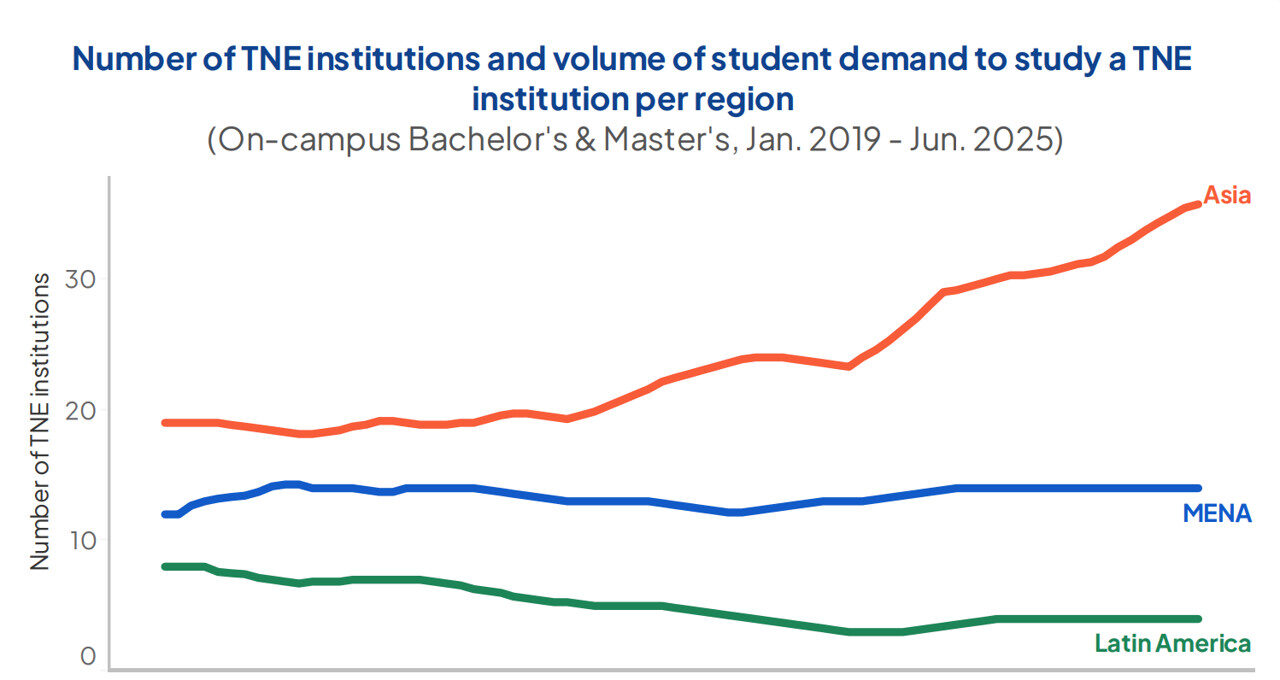

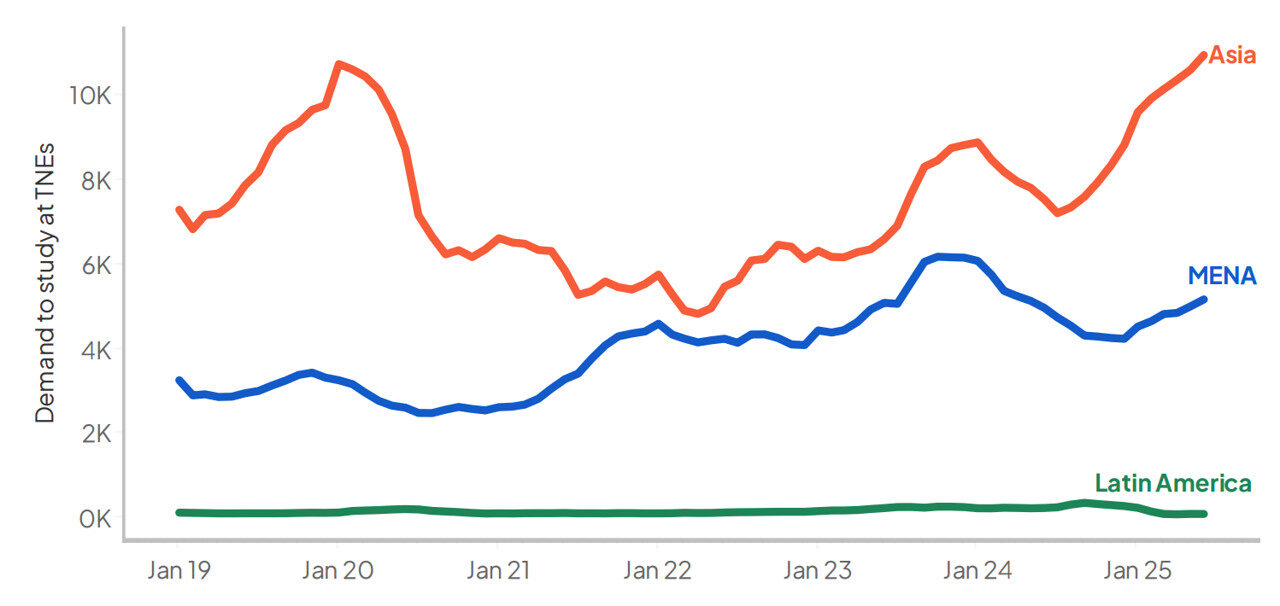

As student demand shifts globally and MENA’s education landscape matures, the region is becoming one of the most dynamic higher-education hubs in the world. The visuals below shows recent Studyportals and British Council research comparing both the number of TNE institutions and the volume of student demand to study at TNE institutions in Asia, Latin America, and MENA. It is immediately clear that Asia consistently has the highest number of TNE institutions, and student interest for TNE, but demand for Transnational education in MENA is growing.

But as Professor Ghorfi’s cappuccino analogy makes clear, institutions cannot rely on light-touch engagement or short-term opportunities. Institutions should stay true to what makes them distinctive, while clearly articulating how they contribute to local needs. The Middle East rewards institutions that bring research, undergraduate teaching, local partnerships, and societal engagement.