Opinion: Tough love or self-sabotage? How Labour’s new Higher Ed policies might affect UK universities.

The Labour government’s new immigration white paper, released on the 12th May 2025, signals a notable departure from previous policy, particularly in its treatment of international students. Designed to recalibrate the UK’s legal migration system, the proposals may instead threaten one of what is historically the country’s most globally admired assets- its higher education sector.

Among the headline changes, are a reduction of the post-study work visa (known as the Graduate Route) from two years to 18 months, a suggested levy on income from international student fees and stricter compliance oversight for universities sponsoring overseas students. These proposed moves have sparked immediate concern across the sector.

University finances under pressure

Universities UK, the representative body for the sector, has been vocal in its opposition, warning that international students are not merely participants in higher education- they are essential to its sustainability. Their fees subsidise domestic teaching and research and their broader contribution to the UK economy is measured in the billions annually.

Imposing an additional financial levy on institutions already grappling with budgets could lead to this being passed onto students in the form of higher tuition costs or cuts to services, degrading the student experience at a time when competition from other study destinations is increasing. The last edition of the Studyportals Global Student Satisfaction report in 2023, which was based on 126 000 student reviews, already saw UK institutions rated slightly below the global average (4.18 vs the global average of 4.21).

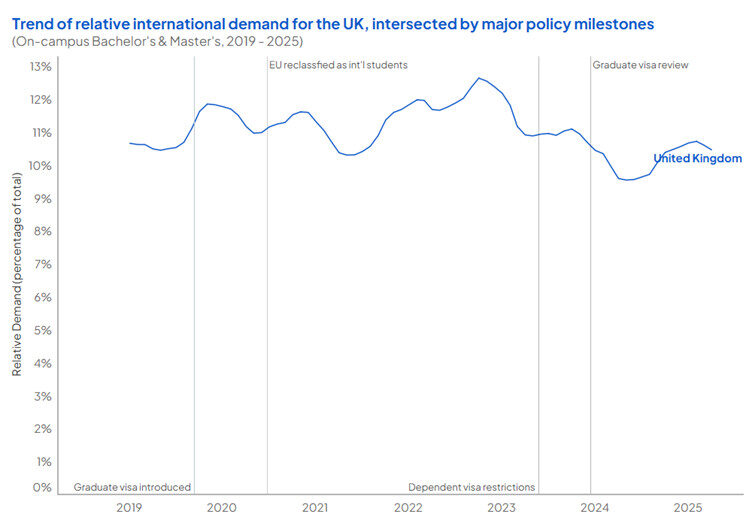

We already know that amendments to post study work rights have historically had a significant impact on student demand: Over the years we’ve seen student demand for study destinations shift in response to policy announcements. In fact, interest in the UK rose by 12% from May last year when the UK confirmed the Graduate Route would stay in place for international students and Studyportals data also showed a drop off in interest on the announcement of restrictions on students bringing dependents.

Cost of reform

The government’s rationale for reform (ensuring the integrity of the student visa route and tackling abuse) is not without merit. During the post-Covid surge in overseas enrolments, some institutions witnessed higher dropout rates and cases where student visas were used as de facto migration pathways.

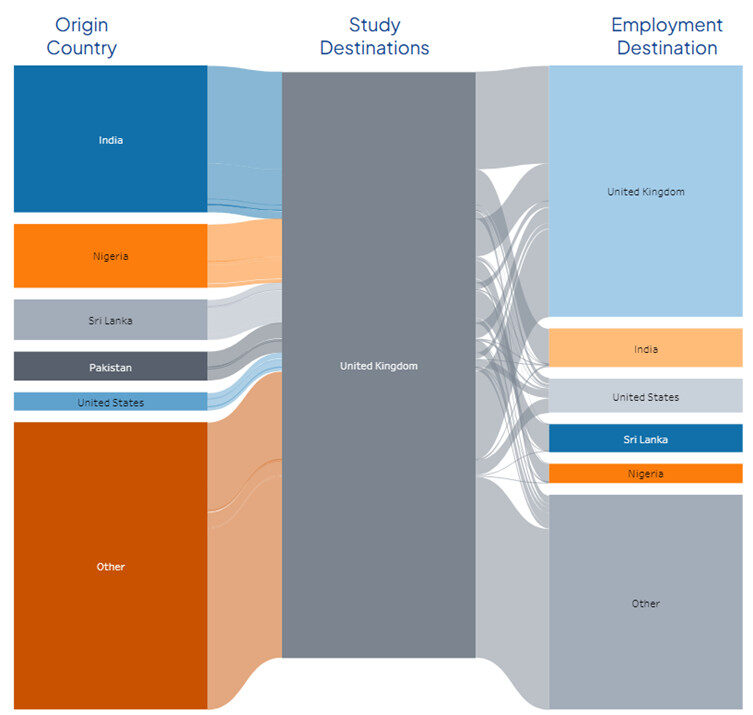

Tightening the system to prevent exploitation is understandable. However, doing so through blanket measures that penalise all institutions and students is a risk. The vast majority of international students come to the UK for legitimate reasons, with serious academic goals and a clear desire to contribute to British society and whilst many do stay for post study work, the majority do not, either travelling onto a third destination, or returning to their home country (according to Studyportals stay rates data).

Messaging Matters: Perception vs Reality

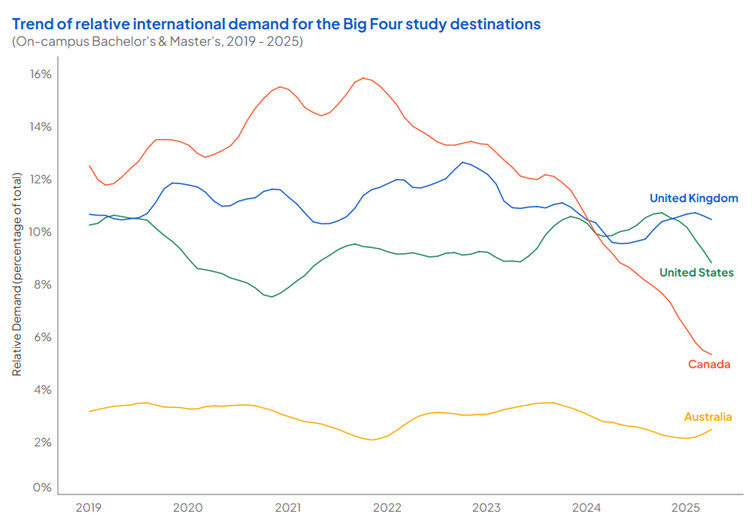

The way these changes are communicated will be just as important as the policies themselves. The UK cannot afford to send mixed messages to prospective students and their families abroad. At a time when global competition for international talent is fierce, negative headlines and confusing policy shifts can quickly erode trust, as we have seen in some of the other ‘Big 4’ study destinations.

Clear and proactive communication about the UK’s continued openness, the enduring value of its degrees and the career opportunities available through routes like the Graduate Route is essential. With the shorter length of the Graduate Route, some international graduates from universities outside the UK now have greater post-study work rights (via the High Potential Individual visa) than those who studied at UK institutions. The country’s brand as a welcoming and world-leading education destination must be actively protected.

Raising Standards

One element of the white paper that has been cautiously welcomed is the emphasis on improving recruitment and compliance standards. Mandatory participation in the Agent Quality Framework (AQF) could bring much-needed consistency. While most institutions already endorse the AQF’s guidelines, enforcement has been inconsistent and some universities still fail to disclose their relationships with agents or provide students with proper complaint mechanisms.

If this proposed policy shift leads to greater transparency and accountability in international recruitment, it will be a positive development. However, it must be implemented thoughtfully, without creating further bureaucratic hurdles that deter engagement or damage trusted partnerships. It’s not clear currently, for example, how many Universities will be affected by the tightening by 5% on the key metrics of the Basic Compliance Assessment framework or how long Universities will have to act if they fall outside of the new thresholds, to avoid losing their sponsor licence.

Student interest from Europe for the UK has still not recovered after Brexit and remains over 30% down. Institutions across the UK have invested heavily in diversifying their recruitment beyond a handful of major markets, working to include students from underrepresented countries and communities. Adding new layers of complexity and risk to the visa process, particularly for students from regions with historically lower visa approval rates, could discourage applications from precisely those markets the UK hopes to grow. If institutions are punished for external factors beyond their control, it may lead to a retrenchment to ‘safe’ markets and a loss of diversity on campus.

Visa refusal rates in 2024 reveal a complex picture shaped not just by where students come from but also by the level of study they pursue. In Nepal, a rapidly growing recruitment market for the UK, only 1.3% of Master’s visa applications were refused, compared to a striking 10.9% for Bachelor’s. A similar pattern appears in Zambia, where rejection rates were 17.3% for undergraduate but just 6% for those applying to Master’s programmes. Conversely, Nigeria shows higher refusal rates at the Master’s level. The hope is that already resource-constrained universities can better support students through the visa process, rather than avoiding recruiting students from markets more likely to face visa denials.

A Call for Consistency

The government’s desire to manage migration and protect the integrity of the system is valid. Amid the mounting pressures of funding and immigration control, it is vital that UK universities remain committed to the sustainable and responsible recruitment of international students. This means attracting students who are well-matched to their programmes, supporting them through to completion and ensuring that their academic and personal outcomes are prioritised but policy must be shaped by both principle and pragmatism. International students are not just temporary migrants and not just ‘cash cows’- they are future researchers, innovators, and global ambassadors for the UK. Any strategy that risks pricing them out or pushing them elsewhere must be carefully reconsidered. What’s needed is a measured, collaborative approach that safeguards national interests without sacrificing the global prestige of UK higher education. The sector is crying out for a period of policy consistency, which appears to be some way off. There remains multiple unanswered questions and clarity will urgently be required for stakeholders on all sides.