A new wave of Indian students studying abroad

This article originally appeared on CNBC. Rahul Choudaha is the Executive Vice President of Global Engagement and Research at Studyportals.

More than 5 million international students were studying outside their home country in 2016. With over 3,00,000 Indian students studying overseas, India is the second largest source of international students after China. However, in the recent times, the political turmoil triggered by the results of the UK’s referendum to leave European Union or Brexit and the American Presidential elections has also created an environment of restrictive immigration and visa policies in these countries. Will the number of Indian students studying abroad continue to grow in this environment?

A shift in destination preferences

The total number of Indian students overseas increased from 66,713 in 2000 to 3,01,406 in 2016, based on the analysis of data from UNESCO Institute of Statistics. This translates into 2,34,693 more students overseas in 2016 as compared to that in 2000—at a robust average annual growth rate of 22% in a span of 16 years. The growing aspirations of Indian students to access to global education reflects an expansion of high to middle-income families.

While the overall number of Indian students abroad has increased, it also experienced a phase of decline as an aftereffect of the global financial recession. The number of Indian students reached its peak of 210,649 in 2010 and then declined until 2013 to reach 190,358 students. Since then Indian students overseas started growing again to cross 3,00,000 in 2016.

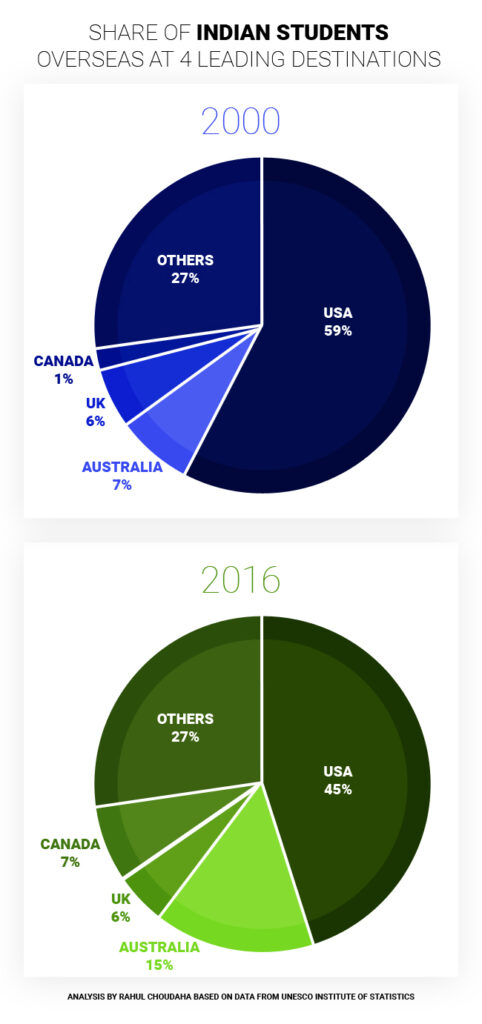

Studying in the US is a dream of many students and families. In 2000, 59% of all Indian students overseas were enrolled in the US universities followed by 7% in Australia, 6% in the UK and less than 1% in Canada. This indicates a clear preference for the US as a destination for Indian students. This is primarily due to a high preference for master’s degrees in STEM programs which also offers pathways to work in the US through Optional Practical Training (OPT) and H-1B visa.

However, by 2016, the share of Indian students in the US dropped to 45% and the UK remained stagnant at 6 percent. In contrast, Australia gained to reach 15% and Canada to 7%. In other words, much of the growth in demand to study overseas was absorbed by Australia and Canada at expense of the US and the UK.

Influence of immigration policies

One of the biggest reasons for this shift in the share of Indian student overseas had been the pro-immigration policies of Canada and Australia. Majority of Indian students are highly-price-sensitive, value-maximisers who are constantly trying to search for options that lower cost and increase career opportunities. And, hence they are more sensitive to immigration and work policies.

For example, Canada’s Post-Graduation Work Permit Program (PGWPP) introduced in 2006 allows students to gain work experience which qualifies for permanent residency in Canada. Likewise, from 1999 onwards, Australia’s point-based immigration policies were designed to encourage international students to pursue a permanent residency in Australia.

On the flip side when the UK announced the abolition of post-study work rights, the number of Indian students has plummeted from a peak of 38,677 in 2011 to 16,655 in 2016. This steep decline was so sharp that the number of Indian students in the UK in 2016 was same as that in 2005.

New segments of growth aspirations

The future demand for international education remains strong among Indian students. In 2018, over 17.7 million students used Studyportals to search for Master’s degrees and about 5.7 million – for Bachelor’s programmes. Our data shows an increase of 37% and 77%, respectively, from users located in India.

While the demand is strong, the unwelcoming visa and immigration policies pose a significant hurdle to translate that aspiration into reality to study abroad. India is at an inflexion point where two broad segments of students are emerging. The first segment is the traditional segment of price-sensitive, value-maximiser. The other emerging segment is the prestige-conscious, experience-seeker.

Value-maximisers will continue to search for options which offer more “value for money” mostly through master’s programmes. For example, in addition to traditional destinations, this segment will seek alternative destinations in the Middle East, Asia and Continental Europe offerings English-taught Programmes. For example, the number of Indian students in Germany has increased threefold between 2010-11 and 2016-17 to reach 15,529 students. Likewise, in line with the presence of large Indian diaspora in UAE, 30% of all international students are from India.

The new emerging segment of experience-seekers is concentrated at undergraduate level and fields of study beyond engineering and computer science. These students have higher financial resources to fund their education and are relatively less concerned about immigration and immediate work opportunities. Consider the growth in the number of Indian undergraduate students at University of British Columbia from 200 to 726 students — a 263% increase in just four years between 2013/14 and 2017/18.

In sum, the growth momentum of Indian students studying overseas hinges on their ability to afford overseas education. This, in turn, relies on the economic growth of India which will support the expansion of experience-seekers while favourable immigration and visa policies in destination countries will attract value-maximisers. Either way, international education is a life-changing experience which more Indian students should not only aspire for but also get access to.

For more updates, follow us!